This is Part 2 of our series called ‘Defining Minimal’. To read part one, click HERE.

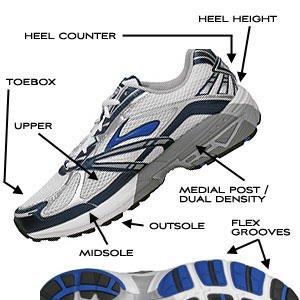

One of the key purposes of this series is to understand what ‘minimal’ actually means (and also what it does NOT mean). Before we can do that, however, we must understand running shoe terminology in general. We covered that in the past – HERE. If terms such as ‘posting’, ‘upper’, and ‘pronate’ sound foreign to you, we highly suggest you read that article before continuing with this one.

Give Me Support

Raise your hand if you or someone you know has ever asked for a shoe with ‘support’. Give me support! A secondary term might be ‘protection’.

To some, simple the appearance of cushion is enough. The taller the sole, the more supportive the shoe is, right? More important to this discussion, it seems that a fair number of people equate ‘support’ with ‘less chance for injury’. We’re not weighing our opinion either way – just making the point known.

In fairly recent times, a second camp has emerged. They equate ‘supportive’ shoes with more chance for injury. Our feet were meant to be naked! Our shoes must be flat, thin, and flexible. Only then can our feet and bodies function properly – which leads to fewer injuries. Support-be-damned!

Who is right? One, both, or perhaps neither? The difficult part of this discussion is the fact that there are a million N=1 examples to support both sides – and every possible iteration of every side. If we all ought to agree on one thing, it is this: Clearly – there is no single right way for everyone.

Those points aside, there are people on both sides of the fence who appear to be generalizing or playing on a slippery slope. I have a problem with that. Many – but not all – of them aren’t defining their terms well enough. Do you love supportive shoes? Do you hate them? What is it – specifically – that is the problem or godsend?

Dissecting Support

Let’s take an abridged glance at the common technical features that contribute to the support that a shoe provides:

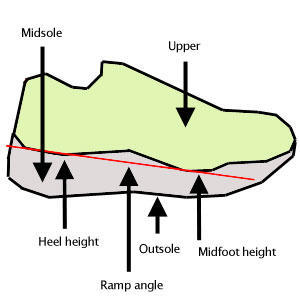

1. Ramp Angle (or heel-to-toe offset, or ‘drop’)

2. Arch height and shape

3. Sole thickness, material, and flexibility

4. Posting amount, density, and location

5. Last shape

6. Heel counter design

7. Upper thickness and flexibility

8. Insole design, material, thickness, and flexibility

If you are unfamiliar with these terms, we suggest you read the article, Tech Footwear Demystifier linked at the bottom of this page.

In the current language of running terminology, the above terms are used in various combinations and degrees that result in three main categories of shoes:

-Neutral or Cushioned

-Stability, Structured, or Guidance

-Motion Control

Think of these categories as a ‘small’, ‘medium’, and ‘large’ in terms of support and weight. Some shoe manufacturers choose to slice and dice the categories beyond three categories, but we will skip that for now.

Where Does Minimal Fit In?

Currently, there are no industry standard definitions for the new crop of so-called ‘minimal’ shoes. Some people even call them ‘barefoot’ shoes. Here and now, we offer what we feel are the minimum requirements for such shoes. We argue that if this category is going to stay around for a while, it should be carved out as its own freestanding entity – simply called “Minimal”.

For a shoe to qualify, it must have:

-No posting

-No built-in arch support of any kind

-Total thickness <10mm at any point – including insole, midsole, and outsole

-Weight <8 oz per shoe

-No rigid heel counter

-Shoe must be able to fold in half across its length

The final attribute (‘shoe must be able to fold in half across its length’) – might not be attainable in the smallest sizes of some otherwise very minimal shoes. We understand this. The spirit of that line is simply to say – the shoe must be very flexible. Rigid track spikes to not qualify.

By these definitions, a Vibram Five Finger shoe is most definitely minimal. As are the Vivobarefoot Aqua Lite, or the Altra ‘The Adam’ shoes. Heck, even my old Asics tai chi shoes fit in there. ALL of these shoes are super light, super minimal, and behave in a similar manner. They all make the draft. If a shoe is missing any of the above ingredients in their sauce, it is not minimal.

But, what about all of the other ‘minimal’ shoes?

Feel like our standards are a little rigid? Perhaps our club is a little bit too exclusive? Sorry, but here at Slowtwitch, the champagne room really IS only for the super elite. No roommates’ friends allowed.

We do feel, however, that there are many other shoes that trend towards minimal that have plenty of value. In fact, there are certain facets of these shoes which we feel sit squarely in the future of most running shoes.

Let us be perfectly clear: Low ramp angle does not equal minimal.

One more time: LOW RAMP ANGLE DOES NOT EQUAL MINIMAL.

If there is one key message for this entire series of articles, that is it. Too often in recent history, we’ve seen shoes called ‘more minimal’ than another shoe. All of a sudden, this idea of ‘minimal’ has spread around like poison ivy, and we’re seeing it everywhere. This editor’s opinion is that many very well-meaning folks read books like Born to Run, saw that the concept made perfect sense to them, and wanted to get on the program. The only problem was that, for some, their bodies didn’t let them. As Matt Ebersole mentioned in Part 1 of this article, pain is a great teacher. However – after speaking with many people who want to go minimal, at some point they also just want to run without pain.

So what happened? Manufacturers wisely responded. New Balance created the Minimus line. Brooks made Pure Project. We found new choices from Inov-8, Altra, Nike, and others. Many people simply started switching from a stability trainer to a neutral racing flat. That’s all fine and dandy with us – the market was working through challenges and coming up with new solutions. As far as we’re concerned, people can run in whatever they want to.

What doesn’t sit well with us is calling these shoes ‘minimal’. There emerged a single facet of minimal that people seemed to be latching on to, which was low ramp angle. Some people (but not all people) wanted flatter shoes. Maybe that meant moving from a 12mm shoe to an 8mm shoe – or a 6mm shoe to a 0mm shoe. All we’re arguing is this: Calling a shoe ‘minimal’ simply because it has a lower ramp than a 12mm training shoe doesn’t fly.

Next Generation of Running Terminology

Defining minimal shoes was the catalyst for realizing that the current naming scheme for ALL running shoes has not kept pace with what runners want. Similar to buying a bike based on stack and reach (rather than, “I ride a 54”), it is time for a naming system based on numbers and real attributes. In the modern age of running, people want to know three things – ramp angle, sole thickness, and whether or not that sole has any built-in posting. Currently, manufacturers offer a million and one different support features, and that’s great. If you’re a moderately mild pronator on every other Sunday, they have a shoe for you.

If you want to know the ramp angle of the shoe, there is about a 30% chance that the manufacturer will tell you on the spec sheet. If you want to know the actual thickness of the sole, your chances get even worse.

This being the case, we offer up our ST-certified shoe naming scheme.

Ramp Angle

Front and center in this new naming scheme is ramp angle (a.k.a. ‘drop’ or ‘heel-to-toe offset’). We offer four categories:

High Ramp: Height differential of 12mm or more

Mid Ramp: Height differential of 7-11mm

Low Ramp: Height differential of 2-6mm

No Ramp: Height differential of 0-1mm

Note that the ‘No Ramp’ category includes 1mm shoes simply to account for manufacturing error in flat shoes. We don’t suspect that anyone is going to market or sell a true 1mm drop shoe.

The Saucony Virrata, pictured below, is a No Ramp shoe, but is most definitely not minimal.

Sole Thickness

We also feel that people want to know the overall thickness of their shoe. A Vibram Five Finger and a Saucony Virrata have the same non-ramped sole, but there is a 15mm difference in thickness between the two. That’s worth knowing.

As such, we suggest that the average sole thickness be listed for every pair of shoes. Note that this number ought to include the thickness of the outsole, midsole, and insole combined.

A shoe with a 12mm forefoot and 24mm heel has an average thickness of 18mm. A Hoka Bondi is 29mm and 35mm, respectively, for an average of 32mm. Listing this average height immediately gives the consumer an idea of what they’re buying.

Stability and Posting

Finally, the third part of the equation relates to stability – a shoe’s ability to combat pronation for you. We support a simplification of the current nomenclature. We suggest narrowing the current three or four categories down to two:

Neutral: The shoe’s structure and materials do not provide any intentional resistance to the runner’s natural pronation.

Guidance: The shoe’s structure and materials do provide some measure of intentional resistance to the runner’s natural pronation.

Why only two categories? We generally do not have an issue with three, nor are we attempting to kill a category. The simplification is for the buying process and to promote understanding of running shoes. As a consumer, we want to start from few options and work to many. Let’s start broad – are we looking for a road bike or a triathlon bike? Then, long-and-low or short-and-tall? THEN – we can start talking about minute details between models.

With running shoes, the first decision ought to be similarly simple. Does your running stride suggest that you need any sort of ‘assist’ in this area? If the answer is ‘yes’, we are just happy as clams if a manufacturer wants to offer more than one option of foam density or last shape in the Guidance category. That is up to them. We chose the name ‘Guidance’ for the very reason that it both clearly suggests what the shoe’s intention is, and also remains open to interpretation by the manufacturer.

The other part of this simplification is an understanding of reality for manufacturers and retailers: You can only have so many SKUs. People seem to be asking for more options in ramp angle, and our guess is that this will likely kill some duplicate options elsewhere in manufacturer’s lines. We always leave the door open to be proven wrong, but it doesn’t seem realistic to us that many manufacturers would offer four different levels of posting in a mid height, Low Ramp shoe… and every other possible height and ramp of shoe.

Real World Examples

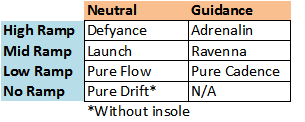

What might this naming scheme look like in the real world? How do current shoes fit in? As an example, I made a table for current-selling Brooks shoes:

On top of this chart, you can apply shoe thickness however you want. There is no reason that any cell on the chart can’t have 4mm or 40mm average thickness. If you want a High Ramp shoe, why should it be super thick – or if you want a No Ramp shoe, why must it be thin?

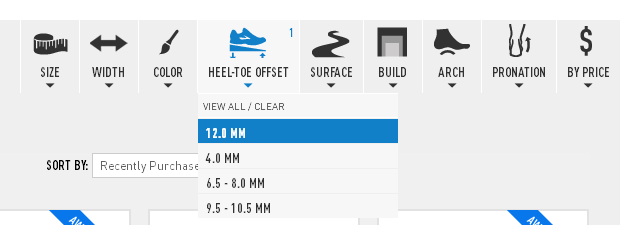

The main reason I chose Brooks is because their website offers a wonderful tool for picking shoes. You can narrow down your search by adding in as many filters as you want – including Ramp Angle (which they call heel-to-toe offset):

You may also notice that there is one cell on my Brooks spreadsheet that is empty. In my opinion, that is the area for market growth. I personally am aware of a single shoe that fills that cell – the Altra Provision. I hope Altra sells the heck out of them, because nobody else has been smart enough to make a competing shoe in the category. In addition, what if someone wants a more cushioned version of that shoe – like a Hoka with No Ramp? As of today, you can’t buy it. In my opinion, we couldn’t see these voids in the past because the old naming system relied on the consumer to decode a cryptic language, or take to measuring every shoe for themselves.

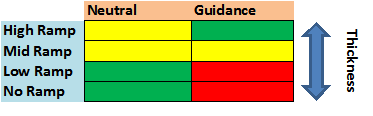

This chart shoes the approximate availability for each type of shoe in the marketplace. It also notes total sole thickness, which trends along with the Ramp Angle (the thicker the shoe, the more ramp it tends to have).

If you want a thick-soled high ramp guidance shoe, you have a million and one options. If you want a thin soled low ramp neutral shoe, shop at will. As you see, once you stray from these norms, the number of options goes down.

If a manufacturer really wants to dive in and offer options to satisfy the savvy modern consumer, the math is easy to do. Say they want to offer two sole thicknesses – 15mm and 25mm. They also want to do three Ramp Angles – 0mm, 5mm, and 10mm. That gives you six shoes. If you want to do a neutral and a guidance in all of these shoes, that makes it twelve total. Of course, it may not make sense to offer every single possible option, but the point stands.

We admit that the running shoe industry is a big ship to turn. Ultimately, consumers will determine where it goes by voting with their purchasing dollars. What do you think? Would you be more apt to shop for a certain brand if they clearly showed ‘the numbers’ for what you’re buying?