This is the first in a mini-series on evaluating popular “hacks” in triathlon. First of all, I hate the word “hack.” My eyeroll alarm goes off every time I hear it. But some of the ideas behind “hacks” aren’t necessarily terrible and are worth serious evaluation. So I’ll use these articles to discuss if I think they’re actually good ideas, or if they deserve a thumbs down.

Low Carb Fueling

Disclaimer: There are dozens of articles that do deeper dives into this, and my goal here is not to uncover new evidence. I’m just giving my opinion on all of it, having read those articles on it and having had many conversations about it.

The latest diet craze in triathlon is “Low carb, high fat!” and “Ketosis!” They seem to be an offshoot of the larger “carbohydrates are the devil” fad that’s been sweeping across America for the last fifteen or so years. These dietary habits can work for daily living and even help with some specific medical conditions (such as epilepsy and diabetes). Some people have tried to extend those ideas over into triathlon. One of the driving forces is the mistaken belief that ingesting sugar during exercise spikes blood sugar and insulin levels, and leads to increased body fat.

This is false.

Any sugar you’re ingesting during intense exercise is quickly used as fuel, and doesn’t cause the associated blood sugar and insulin spikes seen from ingesting sugar while sedentary. Additionally, there’s the idea that if you go low/no carbohydrate, then you’ll need to carry less and the feeding process becomes more streamlined during training and racing. And yeah, this actually sounds kinda nice.

However, the point of fueling isn’t simply “what’s the smallest amount of fuel I can carry?” The point is “how can I get to the finish line fastest?” And for what it’s worth, between pockets, bento boxes, and on-course aid stations, having access to enough carbohydrate fuel should never be an issue for you in a triathlon unless you’re dazzlingly incompetent. (Editor’s Note: turns out I have a new line to add to my Twitter bio.)

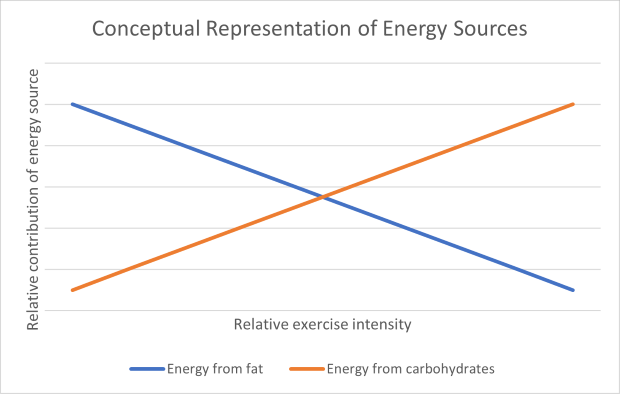

So those are reasons it might not be helping you as much as you think, but what’s really going on here? The main issue with going low/no carbohydrate and relying on body fat stores is that fat takes longer for your body to metabolize than sugar, and so you get less energy per unit of time than from sugar metabolism. This is where we get into the world of sliding scales. As exercise intensity increases, your need for rapid fuel processing also increases. Energy metabolism from fat becomes self-limiting in a manner, because your ability to do work is limited by the rate that your body is able to provide energy to muscles. Essentially, fueling from fat lowers the ceiling on the intensity of work you can produce in racing events.

For low-intensity work (say hiking or slow jogging), then fat as your primary fuel is fine, because at these intensities, your body doesn’t need energy as rapidly. The problem here is that a well-executed triathlon is not a “low intensity” type of activity. Yes, even Ironman is relatively high intensity, especially as you get to elite competitive levels of the sport.

Now, that’s not to say you ONLY burn fat or ONLY burn sugar during an Ironman. It’s always going to be a blend of both, and then we have to ask ourselves “how do we want to push the balance one way or the other by adjusting our fueling?”

Proponents of low/no-carb fueling methods love to trot out lab testing results showing changes in fat metabolism during exercise over time after athletes engage in low/no carb diets. That’s certainly interesting, but I have to respond with 2 questions:

1.) What physical and mental damage was done to the athlete in the process of achieving this metabolic shift via starvation workouts? (I know of 2 pros whose careers were essentially ended by the stress of trying to force themselves through “starvation workouts” to alter their fat/carb energy profile)

2.) Can you show actual race performance improvement attributable to low/no carbohydrates during a race?

I’ll admit that despite many failures, there are a few athletes who have been fine with this approach, and there is some interesting research suggesting that low/no carbohydrate fueling could lead to minor performance improvements. But stepping back and looking from a bigger perspective, I don’t believe this approach is worth the risks and downsides that come along with it. A good way to think about aspects of performance is to think of them as “dials.” So ask yourself, have you already turned all of your other dials up to 11? Things like “durability”, “pacing strategy”, “tactical awareness in the water”, “body comp”, “bike position”, etc.

Unless your name is Jan Frodeno or Lucy Charles Barclay, the answer is likely “no.”

But if you somehow have ALL of your dials at 11, then yes, switching to a low/no carbohydrate fueling strategy may provide you with the most marginal of gains.

Stepping back even further: One of my guiding principles is “don’t let any workouts or races be compromised by nutrition.” Your workout is a small window of time where you get to stress your peripheral systems, and if you’re not giving your body the fuel it needs to achieve your workout targets, then you’re missing chances to stimulate adaptations. And then beyond that, I hope I don’t have to explain why it’s a bad idea to allow yourself to have nutritionally-limited races. You’ve put in a TON of work to get ready for race day. Don’t risk submarining your race with nutrition experiments that could backfire and cost you far more time than they could ever potentially save you.

Final ruling: Low/no-carb fueling may have marginal benefits in lower intensity-events, but decades of athletes trying different fueling plans, and basics of human energy metabolism, suggest that it’s likely not worth the risks associated with it.

Sleeved vs Sleeveless Wetsuits

Wetsuits undeniably make people faster swimmers. That is not debatable. However, things get interesting when you start talking about full-sleeve vs sleeveless. To frame our debate here, let’s talk about *why* wetsuits make you faster. First and foremost, they allow swimmers to passively have great body position in the water. There is no energy or skill required on the swimmer’s part: a wetsuit will prop their hips up to the water surface and give them a lovely and streamlined body position. This is the main source of speed gained from wearing a wetsuit (don’t believe me? slap on a pair of floaty pants for some pool workouts and see how dramatically your times improve just by having your hips swaddled in neoprene). Beyond body position, there’s also the fact that the outer coating used on wetsuits is more hydrodynamic than skin, so there’s less friction drag acting on your body. The outer material accounts for a 15-20% reduction in friction drag compared to skin. (Toussaint, et al, 1989).

For the sake of argument, let’s invent some numbers (these are obviously estimates, because it’s going to be different for each swimmer and each wetsuit, but for our purposes, these numbers are close enough). Let’s start with a swimmer who gains 7 seconds per 100 meters when wearing a wetsuit, which is a typical number. Let’s say 70% of those gains are from improved, passive, body position, and 30% is from reduced friction drag. So roughly 2 seconds per 100 is gained from the reduced friction drag, and maybe 1/6 of the material is on your arms (so 1/6 of that 2 seconds would be from the arm material). In real world terms, where does this put us? If a wetsuit is giving you 7 seconds per 100 meters, that means the material on the arms is responsible for maybe 0.3 seconds per 100 meters.

Is there a real, measurable, benefit gained by wearing sleeves? Absolutely. But the problem is that that argument is too narrow and ignores some important factors. The two other factors that MUST be considered are wetsuit fit and body temperature. First of all, fit is important. Every wetsuit manufacturer insists that they have a suit that fits you perfectly.

This is simply untrue.

Does every manufacturer have a suit that you can fit over your body and swim in? Yes. Does every manufacturer have a suit that you can fit over your body and swim comfortably in? No. Just the slightest bit of shoulder restriction, over 2.4 miles in the water, is going to gradually add up and increase your overall fatigue levels. And with body temperature regulation, everyone is going to have their different comfort levels, but if the water is above 67-ish degrees, I feel like a lobster boiling in a pot if I’m wearing a full sleeve. So do I gain 0.2 seconds per 100 from the sleeves? Sure. But then I lose 2 seconds per 100 from overheating in 71 degree water. That 0.2 seconds of gain from the sleeves isn’t looking so great anymore, is it?

So what’s the takeaway? Full-sleeved are faster in lab conditions and often also faster in real world conditions for many people, but not for everybody. If you’re super comfortable and not overheating in your full-sleeve, then go on with your bad self and keep using it. But if you feel *any* restriction, constriction, or overheating, don’t be afraid to switch to a sleeveless. Not only is sleeveless cheaper than full sleeve, it may actually be faster for you. Or, if you really want to get extreme with it, try this fun game: next time you race a sprint, just wear a swimskin and floaty pants. I’ve done it several times. It’s almost as fast as a full wetsuit in the water, and allows for ultra-fast transitions.

Final ruling: From a hydrodynamic standpoint, assuming perfect fit and water that’s an appropriate temperature, full-sleeve wetsuits are unequivocally faster. But the real world doesn’t always fit into those prerequisites, so sleeveless can be faster in real-world conditions for many people.