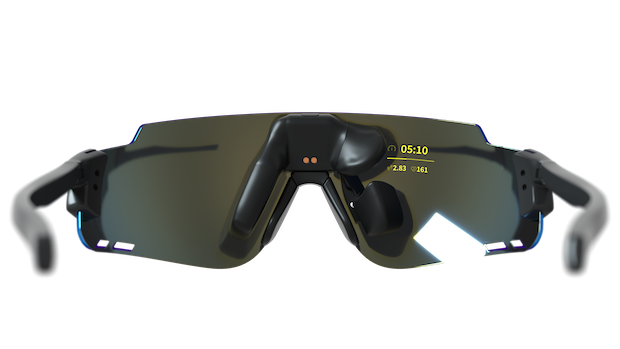

This article is the third in a four-part series, presented by ENGO. In this series, Matt Fitzgerald will teach you how to apply new advances in real-time training data for maximum benefit at various stages of athletic development. Learn more about ENGO here.

The fundamental goal of racing is to find your limit. When you complete a triathlon or other event, you want to look back and say, “I couldn’t have gone any faster.” That might sound simple enough, but given the unique nature of our limits as endurance athletes, achieving this level of performance is difficult. When used appropriately, devices like ENGO that supply athletes with continuous real-time data can help us become better at finding our limit, so we’re less likely to finish races with that dreadful woulda-coulda-shoulda feeling.

Let’s take a quick look at the latest science concerning the limits of endurance performance, and what it takes to find your own personal 100 percent. I’ll then describe three ENGO workouts that I have found to be especially effective in helping athletes find their limit.

The Pacing Factor

The key difference between a sprint, such as the 100-meter dash in track and field, and an endurance race, such as the marathon, is pacing. In both sprints and endurance events, the goal is the same: to reach the finish line as quickly as possible. If you’re a sprinter, the way to do this is to start the race at maximal effort and continue full-tilt until you’re done. But if you tried this in a marathon, you’d never even reach the finish line! To succeed in the goal of completing an endurance event in the least time possible, you must deliberately hold yourself back, racing not at maximal effort but rather at the highest effort you can sustain over the entire distance.

The question is, exactly how much do you hold back? And how do you actually know if you’ve succeeded in completing an endurance race in the least time possible for you on the day? Surprisingly, physiology provides no answers to these questions. Studies have consistently shown that athletes have reserve functional capacity at the point of exhaustion in endurance tests. According to measurements of blood lactate, muscle glycogen, core body temperature, and other potential physiological limiters, athletes are perfectly capable of continuing when they quit a test of this sort. But they don’t feel capable of continuing, and that, it turns out, is what limits endurance performance.

If you want to find your limit in an endurance race, science tells us, you need to make sure you reach the finish line feeling that you can’t continue any longer at your chosen pace or power. But there’s a bit more to it than that. After all, you could walk the first 26 miles of a marathon and then sprint the last 385 yards and you would cross the finish line feeling that you couldn’t go a step further.

A second hallmark of a perfectly executed race, besides feeling completely gassed at the finish line, is consistent pacing. While no athlete ever maintains a perfectly steady output during competition, studies indicate that the steadier an athlete’s pacing is overall, the better they perform in races. The reasons for this are complex, but the long and short of it is that an athlete has only so much energy they can pour into a race, and consistent pacing makes the most efficient use of this limited energy supply.

In summary, you know you’ve found your true performance limit in a race if you managed to distribute your energy very evenly, and in such a way that your rate of perceived exertion (RPE) increased linearly throughout it, culminating in maximal subjective effort (i.e., the perception that you were trying as hard as you possibly could) at the end.

ENGO Workouts to Help You Find Your Limit

Now that we’ve established what it looks like to find your limit in a race, let’s talk about how to get better doing so. Here are three workouts I’ve found to be especially effective for this purpose. While you don’t need ENGO to do them, they’re much easier to execute if you’ve got the relevant data continuously within sight in a heads-up display, and you won’t need to break stride or change body mechanics in order to read a watch.

Long Accelerations

Traditional accelerations are quite short, consisting of 10- to 15-second ramp-ups from a moderate pace to a full sprint. Long accelerations stretch this process out over several minutes, presenting a unique physical and mental challenge. On the physical side, long accelerations benefit athletes by exposing them to a full range of intensities within a single workout. On the physical side, they test and improve athletes’ ability to precisely control their effort. Here’s an example of a long accelerations workout:

15:00 warm-up

6:00 acceleration from moderate effort to full sprint

1:00 rest

4:00 active recovery

6:00 acceleration from moderate effort to full sprint

1:00 rest

4:00 active recovery

6:00 acceleration from moderate effort to full sprint

1:00 rest

15:00 cooldown

To do this workout with ENGO, configure the display 1 to show your current pace (running) or current power (cycling or running) as the primary metric in your screen (or “dashboard”). As you work out, keep your eyes on the heads-up display and try your best to sustain a gradual, continuous increase in pace/power that culminates in a maximal effort at the very end. This is exceedingly difficult to do to perfection (most athletes accelerate too quickly the first time, running out of “gears” before the end of the acceleration), but with repetition you’ll get better, and as you get better at this specific workout, you’ll get better generally at approaching your limit.

To assess your execution in a long accelerations workout, check out your pace or power graph afterward. You should see a line that ascends shallowly and steady with no dips or plateaus.

With repetition, ENGO makes it possible to align the effort you’re able to observe in real time with the curve that you see in the post-workout review.

Stretch Intervals

Stretch intervals are time-based high-intensity efforts where you try to cover slightly more distance in each repetition of a set. The last rep is an all-out effort, and the aim is to complete the first rep at an output that leaves you with just enough room to increase your output incrementally without hitting your limit before the last rep. Here’s an example:

15:00 warm-up

10 x 0:30 stretching from hard to all-out/2:30 active recovery

15:00 cooldown

If you do stretch intervals outdoors, I recommend that you drop a small, brightly colored object (such as a sock) at the end of each rep to mark the distance covered, then go back to the same starting point for the next rep. If you do them on an indoor bike, keep track of the virtual distance covered in each interval. (Note that stretch intervals aren’t suitable for motorized treadmills because the speed is preselected, removing the self-regulation element.)

To do this workout with ENGO, configure the display to show lap pace (running) or lap power (cycling or running) as the primary metric. Note that ENGO’s ActiveLook companion app manages laps differently for Apple and Garmin, however laps are available for both platforms. Complete the first interval at the highest effort that leaves you with just enough room to push a little harder in each subsequent interval. Drop your marker at the endpoint (if applicable), note your lap pace or power for the interval, and aim for a slightly faster pace or power that results in your covering a bit more distance in the second rep, and so on.

In a perfectly executed set of stretch intervals, the lap pace in each rep is just a few seconds per mile faster than the preceding, or the lap power just a few watts higher, and the last rep is a maximal effort. As with long accelerations, you won’t nail the execution the first time, but with repetition you’ll get better, and as you do, you’ll get better at finding your limit.

Locked-In Tempo

The locked-in tempo is a twist on the traditional tempo workout, where you try to maintain a perfectly consistent pace or power output throughout. Remember, a steady distribution of effort is a hallmark of perfect race execution, and this workout is an effective way to improve this ability. Here’s an example:

15:00 warm-up

15:00 @ lactate threshold pace/power

5:00 easy

15:00 @ lactate threshold pace/power

15:00 cooldown

If you don’t know your exact lactate threshold pace or power, just pick a number that is close to the fastest pace or highest power you could sustain for one hour in a race situation. To do this workout with ENGO, you’ll use the same display configuration as you do for Stretch Intervals to show your current pace (running) or current power (cycling or running) as the primary metric. Focus on the display, and try to lock in to the target pace or power from the start to the finish of each tempo block. Also pay attention to your internal perceptions of effort and output; this will help you develop a better sense of what it feels like to hold a steady pace.

The Ultimate Test

ENGO and similar devices are not only useful for training athletes in the ability to find their limit while training. They’re also helpful on race day itself. In the final installment of this series, I will offer tips on racing with ENGO.

Learn More about ENGO, or make a purchase, here.