Dear Reader: This is, more or less, a podcast in writing. I state a thesis, Josh Poertner (Silca, Marginal Gains Podcast) replies; I reply; Josh finishes. We do this over email and did this recently on the topic of tubeless wheels with hookless beads. To be clear, neither I nor Slowtwitch have any current business relationship with Josh or Silca nor is one contemplated.

Dan writes: Josh, upon reflection this is what I’ve come up with: Bike lubrication is to me like shaving. I hate it, it’s a boring chore and I shave once or twice a week. The only thing I know for sure about bike lubrication is: I’ll almost always choose the quick and easy over the perfect.

What this means in practice is that I’m not often taking the chain off my bike. Certainly the sorts of connection links first deployed by Wippermann but now pretty ubiquitous are helpful and, yes, I own a set of chain pliers for the task. (A pic of my chain pliers is just below, you use these to unlock your chains master link during chain removal; you don’t use them to connect the chain.) Still, I just prefer to leave the chain right where it is until I’m ready to change it. Accordingly, the method for stripping a chain of its factory coating, and then cleaning and applying lube at proper intervals, without removing the chain is an imperative of mine. I don’t think it’s too much to ask a consumer to invest in a pressure washer and an air compressor because these devices are in sync with my hatred of banal chores.

One more stipulation: This is for everyday riding. Forget racing for now and I don’t mind spending a couple of bucks extra for an everyday performance lube. I want a performance product and process; I want that lube to be easy to renew at given intervals; and I want the lube to protect the drive train parts.

Can we start with preparing the chain for lubrication? We’ll talk about lubrication in a minute just, for now, I’ve got this bike, maybe it’s new and maybe I’ve just decided to get religion on the right way to lube. I want to start with the stripping of the factory chain prep because it’s pretty clear that this is critical and I want to know the products and the process. Is it reasonable to assume I can do this without taking the chain off the bike? I ask because it’s unlikely I’m going to take the chain off the bike.

Josh writes: First of all, this is a topic near and dear to my heart, and I also despise shaving, feels like such a waste of time and money just so I can look as average as I did yesterday! I've personally always struggled with this feeling that maintenance activities are stealing from more valuable things like training or more innovative endeavors, but a lifetime of being around aircraft, racecars, and cycling at the highest level has really helped shape me into a true believer that doing the right maintenance in the right way, can ultimately be a huge time and money saver in the long run.

So let's start with factory grease. Chains are lubricated at the factory via 2 means: first, bicycle chains are made at very high speeds with all of the components being sandwiched together and then the pin press fit between the two outer plates. It sounds like machine-gun fire as it happens so quickly, and one of the big challenges for the producers are heat and metal-on-metal galling during assembly, so the chain is sprayed with an assembly lubricant during this manufacturing to help reduce galling of metal surfaces and to keep temperatures under control. This assembly lubricant is generally a lighter weight oil flooded onto the parts as they move through the machine. At the end of the assembly most chains are then also dipped through a heavier grease-type lubricant which has been heated so that it has very low viscosity allowing it to penetrate and coat the entire chain, both mixing with and displacing the lighter assembly lube. There are a million types of greases and additives, and from what we see in our testing the ones chosen by the manufacturers for this final chain coating are biased toward anti-corrosion and metal protection properties than they are to low friction or reduced wear during use. This makes sense from the perspective of the manufacturer: A chain that looks a little rusty after 3-4 years sitting on a shelf is a problem, whereas a chain that runs at higher friction or maybe holds onto road grit when you ride it really isn't.

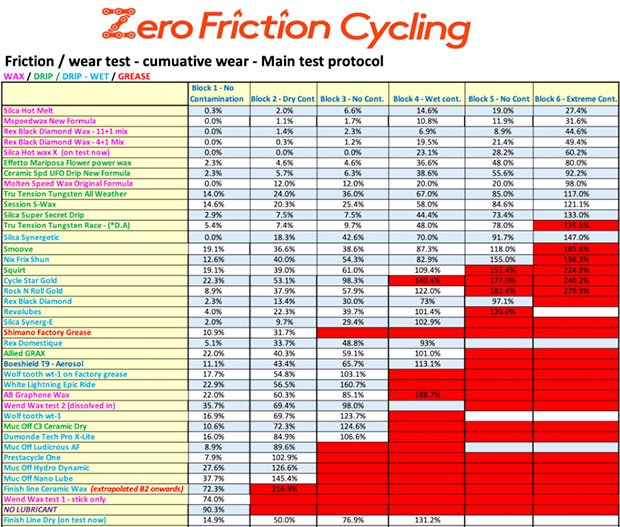

So we have our brand new chain full of this very sticky, viscous, grease, and a lot of the manufacturers say that it's the best lubricant the chain will ever see, which might have been true 10 years ago. Fortunately, we have an independent third-party test lab that looks at these things and he's proven that while factory grease isn't THAT bad, it can no longer be considered good either, and of course it doesn't last forever so we have to eventually put something over top of it.

We see on the ZFC test chart (below) that in Block 1, which is 1000km of clean/dry operating at 250w, factory grease shows 10.9% chain wear. If we are comparing to prior generation lubricants this is actually quite good. If we were in 2010 I'd say factory grease is about as good as it gets, but there are also a whole host of modern lubricants which can run at less than 2.5% wear in that same 1000km test block with a few of those running at a remarkable 0.0% wear in 1000km, and many of those run much cleaner, quieter, and faster than the factory lube.

So for those interested in moving into these more modern lubricants, we ideally need to strip the chain of 100% of that factory grease so we can replace it. Here are the three strategies for doing this (actually four), or maybe more 3 plus 1 for those who want to spend the absolute minimum amount of time on this!

Option 1 (Effectiveness: 75-80% / Time: 2-5 minutes every 50-100km for 1000km). You CAN use oil-based wet lubes over top of factory grease and it will eventually displace the grease. The key here is to add the lube frequently, wiping the chain both before and after adding the lube with a microfiber towel. The wiping before will remove surface contamination that the wet lube might otherwise carry down into the chain, and wiping afterwards helps wipe away any contamination that the new lube might flush out, while also reducing the excess lube on outer surfaces that dirst will want to stick to. Adam at ZFC has shown that applying a wet lube like SILCA Synergetic, NFS, or Rex Black Diamond over top of factory grease will result in roughly the performance of the factory grease for the first ~1000km and then more or less match the performance of the wet lube after that. The key here is to apply the new lube every 50-100km or so for those first 1000km to help speed the transition inside the chain from factory grease to the wet lube. After that, service intervals should be every 250-300km and after every rainy ride.

Option 2 (Effectiveness: 90-95% / Time: ~30-45min one time). You can try to strip the factory grease from the chain while it's on the bicycle and then move directly to a wet lube or drip wax lube. This one is hard because that factory grease is SO tenacious, and we really don't want to use super harsh solvents around the other parts of the bike like hubs, bottom brackets, or any electronic components or connectors. The two best products on the market for doing this are the SILCA chain Stripper, and the Ceramicspeed UFO clean. Both are biodegradeable, surfactant based cleaners that are strong enough to attack the factory grease, but won't damage rubber seals, plastic dust covers, paint, or electronic bits. Both of these can be dripped onto the chain and rinsed off, and both require some time to do the job well, so we recommend 10-20 minutes of contact time between the cleaner and the chain with occasional agitation by backpedaling. You can also use one of those plastic chain cleaning devices with both of these cleaners, again, you just want to make sure to give time for the cleaner to attack the grease. After the cleaner has done its job, you want to rinse well with water to help flush out the residue, if you have a compressor, I'd also blow out the chain to speed the drying process and reduce the likelihood of any corrosion forming inside the chain. You can get about 95% of the factory grease out of a chain by this method if you do it well, but I'd plan on 30-40 minutes to really get it right.

Most important if you choose to strip the chain on the bicycle is to avoid any of the common chemicals you find recommended for stripping a chain on the internet. These include mineral spirits, paint thinner, toluene, acetone, and denatured alcohol. Mainly, all of these chemicals pose some risk to rubber seals and o-rings commonly used in sealed bearings and brake systems, and some of them can be very damaging to wire insulation and grommet seals common to electronic shifting systems. All of these chemicals are also of low enough viscosity that they tend to wick their way inside of areas where you really don't want them like hubs and bottom brackets, under SRAM batteries, etc where they can cause a lot of damage. We actually quadrupled the viscosity of our chain stripper during the testing phase to help ensure that it stays in the chain and also that it doesn't wick its way into places you don't want it, but... it's such a fine line as we still want it to wick into the chain itself!

Option 3 (Effectiveness: 100% / Time: 15min-1 day, one time). Removing the chain to strip it. While everybody feels like this is the most painful way of doing things when they first hear it, I have to say that I've come to believe that it's actually faster and easier, as well as safer to the rest of the bicycle the more that I've done it. The main benefit here is that you do not have to worry about any chemical interactions between what you are using to strip the chain and any other component of the bike. All of the harsh solvents mentioned above work well here if used properly, and while the off-bike method can take up to a few hours of total time depending on how you do it, the actual working time/human involvement is really quite small. If you are starting from a new in box chain, it's even easier, I just drop the chain straight from the package into the solvent and let soak. The key to this method is following a proven recipe. The original recipe was to soak a chain for ~3 hours in mineral spirits, paint thinner, toluene, gasoline, kerosene or similar agitating it frequently, and then shift that chain to a second more polar and water miscible solvent like acetone or denatured alcohol for 10-20 minutes of agitation before allowing the chain to hang to dry. Maybe takes a day in total, but you are actually hands on for less than 20 minutes total including the removal and reinstallation of the chain. Having the chain off of the bike also allows you to use an immersive lubricant like hot wax which is proven to be the best of the best in terms of friction and wear.

Notes and risks with this option: SILCA chain stripper was designed to do this whole process in 10 minutes, and we think it works great but clearly I'm biased! We've also seen good results with Ceramicspeed UFO Clean as an immersive chain stripper. Beware immersive soaking in mineral spirits or the like on a used chain as it can trap any moisture on the chain surface causing corrosion. Also beware water based degreasers especially Simple Green as they can cause hydrogen embrittlement which can lead to micro-crack formation in the metal, I know this sounds crazy, but a number of these water based cleaners are banned from use in aircraft and military due to documented failures. It is never a bad idea to final rinse any chain in acetone or denatured alcohol to help it dry and remove any residues or moisture.

Option 4: (Effectiveness: 100% / Time: 1 minute online plus shipping) Buy a pre-waxed or race prepped chain. This is by far the most expensive option, but certainly the fastest and easiest! There are numerous companies offering this as a service and it's a great option if you are looking to move your entire drivetrain to wax. All of the common pre-waxed chains on the market are hot-waxed, but can be maintained using drip wax lubricants.

Dan writes: For a moment can we limit this to lubrication on bikes during training? Because, those are 99 percent of my rides and my goals during those rides are performance and efficiency on the one hand, and protection and longevity on the other. I want my drivetrain parts to go faster and last longer. I guess as I’ve researched this I’ve come to view the stripping & prep as the less appreciated and more important part of this process. Consequently, I just bought a bottle of Silca Chain Stripper and shall eagerly await its arrival. My plan is, when I wash my bike, I’ll begin with chain stripper sprayed on the chain, and I’ve always previously used generic biodegradable degreaser but I’ll move to the Silca product on the assumption that this is a product more focused to the problem. I’ll use it on my cassette and chain ring teeth as well. Wait 10 or 15min for it to do its thing; the rest of the bike I’ll wash with regular soapy water; I’ll rinse the entire bike with a pressure washer and straight water; dry it with compressed air; then lube the chain and any other parts that need to be lubed.

Let’s say you wanted to lube your pedals. In actual practice do you use something different or, if you’re being lazy like me, will you just use the same lube you put on your chain? The thinking being: I want to lube the pedals with something that doesn’t attract dirt, same as with the chain. But if chain lube is just that specific then maybe you don’t use it on pedals. What say you?

For sure, taking the chain off the bike isn’t as big a deal as it used to be. For the typical consumer, I’m pretty violently against taking the chain off if that chain must be replaced using a press pin. Thankfully today’s master links are pretty universally used and there’s much less chance of user error. But unless I’m mistaken both SRAM and Shimano consider their master links to be single use. Unless upgrading to a Wippermann Connex link this really limits the real-world likelihood that those who’re reading here will take the chain off the bike. So, I do think there is – pardon the pun – a disconnect in the stated best practice in chain prep and the likely practice. This is why I’m being a curmudgeon on the issue of chain removal. Who reading this, right now, has extra sets of master links in their garage?

Racing, okay, if you’re going to do one race a year that’s your A race, then what makes the most sense to me is just buying a prepared chain and then using that chain throughout the rest of the year for training. In this case I suppose the chain stripping step might not be necessary, but I don’t know, you tell me. If I’m using Squirt or Silca lube, for example, if it’s already a wax-based emolument over a chain waxed from the factory, how would you clean that chain now that you’re just using the bike for training?

Josh writes: Once you get the chain stripped and converted to a wax type lubricant, you'll find that training and racing setups are essentially the same. The biggest advantage is possibly the reduced time required to clean the bike, so the little bit of extra work up-front makes race-day cleanup and prep go significantly faster as you have nothing to clean off of your cassette, rings, or jockey wheels. My standard advice for training is to think in 1000km blocks (similar to the ZFC friction test blocks) where you reset the chain every 1000km with a deep clean and a hot wax bath or a deep clean with a layering up of a top drip wax, and then use a top drip wax lubricant every 250km to help keep the chain topped off through the training block. This will get you minimum wear with maximum efficiency and really isn't hardly any work. Then, as race day approaches, wash the bike and reset the chain and lube up for your event.

If you are resetting the chain on the bike, I recommend using a product like chain stripper AFTER washing everything else with soap. One of the key learnings we've had during our 2-year development of stripper as well as our soaps and cleaning products is that the key to it all lies in the residues of the chemicals involved. If you think about the original chain stripping recipe, it was using mineral spirits to soften and dissolve the factory grease, and then moving to a water based degreaser to remove the soften greases and mineral spirits, and then to acetone or an alcohol to remove the residue left by the mineral spirit and water based degreaser. With our chain stripper, we started with a list of degreasing agents that left residues favorable to wax and then tested about 120 of those to find 3 that were very efficient at attacking the common types of base oils, thickeners and additives common to factory grease.

Why it's important to strip the chain last is that most common soaps and other degreaser/cleaners will often leave their own non-favorable residues. We've developed our own residue-free soap that plays well with wax, but it's expensive and might not just be lying about the workshop already. I'd say most commonly we see even top pro mechanics using Dawn or similar dishwashing soap, but if you look at the ingredient list (and MSDS) you will see that Dawn has all sorts of ingredients that can be problematic if left as residue inside the chain, including sulfuric acid, sodium hydroxide (which dissolves aluminum), salt, and in many variants, a skin lotions or oils to keep your hands from being destroyed by those other things. As a result, we recommend cleaning the bike as you normally would, degrease the drivetrain, brush, etc and then finish with a Chain Stripper or UFO clean drip on the chain, rinse, blow dry, and then add the drip wax or other top lubricant. If you are removing the chain, you can just throw it into the stripper while you're doing the rest of the bike washing, so from my experience it generally saves a bit of time to remove the chain and reset it, but as you state, there are possible risks associated with master links, etc, and I agree 1000% that if your chain is fully riveted without a master link, leave it on the bike!

On the master link topic. We've tested the heck out of this and I have personal master links that are 10 uses into their lives without issue and pretty much every SILCA test rider and pro athlete has similar stories (though we do recommend discarding them after 6-8 uses). So on the one hand I'm obligated to say that you need to follow the manufacturer's instructions, but on the other hand I've never met anybody who's broken a master link that was installed multiple times, and we've never had a WorldTour team or pro Triathlete have an issue here either, and that's hundreds of athletes and thousands of races. Having said all of that, I always carry a spare link with me (SILCA multi-tools all have little magnetic holders for them, as do tools from Lezyne, WolfTooth, and I'm sure others). I also always keep a few about in my shop. SRAM and Shimano both sell them in multi-packs, so when I buy a new bike, I get a 4 or 6 pack of them and I generally have 1 or 2 of them left over when I sell the bike a few years later. One way to look at the expense here is that you are potentially increasing life of the chain and cassette by 5-10x by using one of these advanced lubrication regimes, so figuring the new SRAM Eagle cassette is $600 and the chain is $150, the 4 pack of masterlinks for $18.00 looks like quite a bargain!

Pedals. Any of the top drip waxes will also work well on cleat/pedal interface surfaces, so SILCA, CeramicSpeed, TruTension are all great options as they dry clean and hard, our pro mechanics seem to love painting it on with a little brush, but dripping from the bottle works well also. I prefer these to the classic dry lubricants that many of the pedal brands recommend, such as Speedplay, as those dry lubricants tend to be very environmentally harmful and contain PFAS ingredients which you are then tracking about when you walk, especially on Speedplay where it's really the cleat that needs the lube more than the pedal. Many 'dry' lubricants are simply PTFE or other PFAS substances in a strong, thin, fast evaporating solvents like pentane or heptane to help them wick into all the nooks and crannies, so you also need to be careful applying them to the pedals themselves as stray drops on say the spindle can result in the strong solvent wicking its way behind bearing seals where it will begin to break down bearing greases.

Race Day. As you mention, buying a race prepped chain is probably the fastest way to get there, albeit also the most expensive. One thing to consider also is that many of the race chains aren't just pre-waxed, but are run-in for 50km or so first to help debur and remove any excess metal particles that are left from the chain manufacturing, and then stripped and waxed. SILCA, CeramicSpeed, and MoltenSpeedWax all offer similar variants of this concept. However, you can get 98% of the same effect with a hot wax at home, or with a 2-3 layer drip wax application right before race day. We have a great video explaining what this 'Layering Up' is with drip wax and why you want to do it for your key events, but essentially, these top drip waxes are 30-40% water as a carrier, so once they dry, the chain has space in it to add more lube, this makes it both faster and longer lasting and the technique works with all of the top drip waxes already mentioned:

Once you are working with a fully waxed chain and drivetrain, you should never have to strip it again, and in fact, the waxes are so resistant to standard chemicals, that the common stripping methods won't do much to remove wax from the chain. Your best bet to 'reset' a waxed chain is boiling water, I remove the chain, toss in boiling water for 5 minutes and then go straight to hot melt wax. If you are not removing the chain from the bike, you can reset it on the bike with boiling water from a kettle poured onto the chain at roughly the 3 o'clock position of the chainring, all the old wax and grit just fall out of the chain, and you can then go straight to re-lubricating after you blow the chain out with compressed air (or bounce the bike a dozen times or so to de-water it as much as possible).

Lastly, you mention using Squirt or SILCA over a hot waxed or factory pre-waxed chain. The short answer is yes, as mentioned above, you can use a good drip wax is a great way to extend the performance of a pre-waxed or hot waxed chain. However, it should be noted that there are different types of drip waxes out there and not all of them work the same way or will be compatible. First, you have wax-based dry lubes: Finish Line, White Lightning, MucOff and others make these. These are just dry lubes with 80-90% solvent and some manner of wax particles. These generally do not work well over top of other wax lubricants and will soften the base wax if mixed, resulting in the need for much more frequent re-lubrication. They will work in a pinch but I wouldn't build this into a lubrication strategy. Second, you have first generation wax emulsions, which are Squirt and Smoove. These products are a paraffin wax and paraffin/oil mix and both of them are too viscous to penetrate fully to the pins of the chain. Also, both of them remain quite tacky as they do not dry due to the high oil content (which also makes them quite dirty). Both of these products will soften and degrade hot wax, and will only be able to reset the chain to near original efficiency if you use a hair dryer or the like to soften them to the point that they can fully penetrate to the pins. Adam at ZeroFriction has quite a lot to say about this in his report on those products so if you're interested in the details check those reports out. Third, you have the newest generation of products which are largely based on the emulsion/suspension technology that we developed which allows for a high percentage of wax solids to be emulsified into and suspended in a low viscosity water or alcohol (or both) carrier which can have wax percentage of 60-70% AND still penetrate the chain fully. These are the best 'top-off' lubricants for hot waxed or race prepped chains as they all contain paraffin or paraffin compatible waxes in wax safe carriers that allow them to dry to equivalent hardness of the base wax. SuperSecret, UFO 2.0, TruTension All weather, and Effetto Mariposa Flower Power are the products that currently occupy this third and most advanced category.

As I finish typing all this it always feels crazy just how many words can be written about chain lubrication and cleaning. And we're still learning! I feel like we know 1000x more than we knew 5 years ago, but every month we discover something new, or a new technique to improve longevity or reduce friction. The chain lube category right now feels very reminiscent to me of the massive advancement period in aerodynamics in the late 90's and early 2000's where you have a couple of really solid players pushing each technologically, but also conceptually. The same is happening right now with this thing that seems so simple, like something we should have figured out 100 years ago yet is still full of so many unknown variables and questions, which is my way of saying that this is the best of my knowledge today, but I'll bet you that 2 years from now a lot of this will be different.