Love it or hate it, technology is inherently a part of triathlon. In this month’s exploration of triathlon related "hacks," we look at a couple of recent technologies that have been adopted by many athletes but leave even more athletes saying “I have no idea what that is.”

Carbon Plated Running Shoes

If you follow pro racing at all, you may have noticed that the running times have improved markedly in the last few years. In 2009, people’s heads exploded when Matt Reed ran a 1:11 at Oceanside. Sub-1:15 runs off the bike were fairly rare, let alone a 1:11. Now it seems like sub-1:15 is routine, and you have to flirt with 1:11 just to make a men’s podium.

So what the heck is going on? Is it drugs? Unlikely – we’d see similar leaps in swim and bike times. And while I’d be a fool to think that no one is doping, I also refuse to believe that suddenly everyone started doping 3 years ago. (I started doing a deep dive into comparing splits among the three disciplines over the last 10 years, but quickly gave up on that idea when I considered the scope of data necessary to come to statistically significant conclusions. And then how do I account for improvements in bike tech? It was starting to feel like a statistics term paper).

Is it improvements in training technique or nutrition? No, sorry. Running is running and food is food. Maybe you can find 0.5% improvements over several years by tweaking those variables. And more often than not, revolutionary new training and nutrition techniques is a euphemism for we came up with a new doping regimen that the testers can’t detect yet.

Is it “the power of belief”? Yes, that probably plays some role. The classic example of this is the 4-minute mile barrier. Nobody could run a sub-4 mile and a lot of smart people thought it may be impossible. Then Roger Bannister did it, and suddenly every elite middle-distance runner could do it. Heck, a high school runner even went sub-4 within a decade of Bannister’s feat. Belief that you can get through the pain and actually achieve something is much stronger after you see someone else do it. The task goes from “impossible” to “possible,” and this absolutely matters in endurance sport.

Is it the shoes? Nike claimed a 4% performance improvement with their carbon plated shoes, but of course they did, right? They’re trying to make money, so they’ll pay a lab to write a paper with the exact conclusions that help them make money.

But just because they’re trying to make money doesn’t mean they’re wrong, it just means their claims should be viewed with a bit of skepticism. Given that drastically new shoe technology came out at the same time as run times improved sharply, and that every significant men’s and women’s running world record 5km and longer has been broken since carbon plate running shoes were introduced, Nike’s claims sure seem plausible (Pardos, et al, 2021). The idea behind these shoes is that the stiff carbon plate acts to roll the foot forward through ground contact, keeps the toes straight at push-off, and has more of an energy-storing “spring effect” than traditional running shoes (Pardos, et al, 2021).

This relatively well-known articledoes not appear to have any authors with significant ties to major shoe companies, so I’m inclined to trust its conclusions. Cliff’s notes: it comes to the same conclusion as Mars Blackmon: “It’s gotta be the shoes.”

Just about every major player in the distance running game has a carbon model out now (Asics, New Balance, Nike, Hoka, Adidas, Saucony, Brooks, On), and there are surely minor performance differences between the brands and models. But I’m not digging that deep, since those benefits are going to vary based on how each shoe feels to an individual and how its specific carbon plate interacts with that person’s stride. I can tell you that I have a pair of Saucony Endorphin Pro 2’s (as does one of my athletes), and my anecdotal conclusion is that they are magical. I’m not going to say which brand is “best”, because I do believe it’s individual. But I do feel comfortable saying that if you’re not in carbon plated running shoes on race day, you’re putting yourself at a competitive disadvantage.

Reference: Muniz-Pardos, B., Sutehall, S., Angeloudis, K. et al. Recent Improvements in Marathon Run Times Are Likely Technological, Not Physiological. Sports Med 51, 371–378 (2021).

Heart Rate Variability

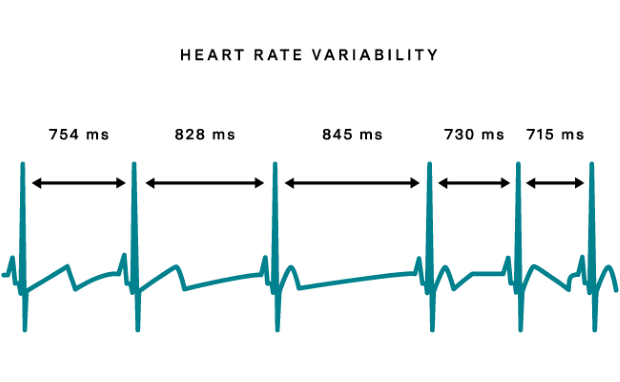

I’m sure you’ve seen people wearing Whoop straps and Oura rings, and you know that those wearables are telling people how rested their body is, tracking sleep, etc. But how do they work? They measure something called Heart Rate Variability (HRV), which measures the variation there is in the time between your heart beats. Yes, you read that correctly. Despite what you may think, your heart does not beat at perfectly regular intervals. However, the variations are so small (on the order of 0.1 seconds from one beat to the next) that we can’t detect those variations without fancy technology.

In general, more variability indicates a healthy and well-rested individual, less variability indicates fatigue or possible health issues. However, it’s important to remember that everyone has their own baseline, and so these devices measure your HRV against your own personal baseline, not necessarily against an arbitrary set point.

A few of my athletes use these devices, and I wore a Whoop strap for about 3 months back in 2018. Here’s my brief review:

Pros:

--The strap was incredibly accurate. When I felt tired, the Whoop app told me that I was tired and needed recovery. When I was peppy and ready to roll, sure enough, the Whoop app told me to go hard in training.

--The sleep-tracking feature is useful. It’s eye-opening (pun intended) to find out how different “time in bed” can be compared to “time actually spent sleeping.”

Cons:

--The need to recharge it every 1-2 days made me somewhat neurotic and it became a major nuisance. Whoop claims to have improved their battery life since 2018, however, so this may not be an issue anymore.

--In order for it to be most accurate, you have to wear it 24/7, which can be annoying.

--Starting at $30 per month, Whoop memberships don’t necessarily break the bank, but they are an expense you need to consider.

Overall:

I like my athletes using it because I can get sleep numbers auto-uploaded to TrainingPeaks. However, there is one significant drawback: it can mess with an athlete’s head. There are specific times in training when I want an athlete to be unusually worn out and want them to continue pushing hard anyways. This is not common, but it happens, particularly during the final weeks of an overload period before a taper starts. If they have a big workout on the schedule during a planned overload period, and an HRV device tells them they should be resting that day, it can have a real impact on their motivation to push through fatigue and complete the planned session. So, as a word of warning, if you’re a coach and you’re putting an athlete through a planned overload (with rest on the back end, of course!), it may be a good idea to encourage your athlete to ignore the HRV data for a few days.

Overall, I didn’t love the Whoop strap for myself and stopped using it. That’s not to say it’s a bad product. Rather, it’s an amazing piece of technology. It just wasn’t for me. I was tired and it told me I was tired. I felt great and it told me I should feel great. I don’t need to pay $30/month for a device to tell me what I’m already feeling. However, for a newer athlete who doesn’t have a developed sense of what their body is telling them, or someone who doesn’t quite have the discipline to hold back when their body is telling them to hold back (read: self-coached athletes), I can see HRV technology being extremely useful at telling you how to interpret what your body is telling you. Essentially, it can accelerate your learning curve for interpreting biofeedback. And if you make a concerted effort to learn from it, it can even make itself obsolete.